–By Cindy Jacobs

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, spiritual music had a profound influence on the development of “new American classical music” as well as perhaps its first effects on the embryonic beginnings of the 20th-century civil rights movement. Part of this interesting history is found in the unlikely intersecting paths of Marian Anderson, Eleanor Roosevelt, H.T. Burleigh, and Antonin Dvořák.

The most well-loved rendition of “Deep River” may be the one by legendary African American contralto Marian Anderson. Having been rejected by the all-white Philadelphia Music Academy, she auditioned to study privately with voice teacher Giuseppe Boghetti. She sang “Deep River” for him and brought him to tears (“Deep River” also was her first recorded song; see below). Boghetti encouraged Ms. Anderson to focus on a European concert career due to the racial prejudice in the United States, and she did so extremely successfully in the 1930s, enchanting Swedish composer Jean Sibelius among others. Sibelius composed pieces for her voice, and conductor Arturo Toscanini told her she had a voice “heard once in a hundred years.” She began to give recitals in the United States in the late 1930s. Even though she was famous due to her European career, she still encountered prejudice; for example, she was not allowed to stay in many hotels in cities where she appeared.

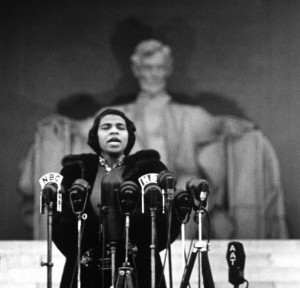

On Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939, Marian Anderson gave a concert at the Lincoln Memorial, after the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow her to perform at Constitution Hall. Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the DAR in protest and, with assistance from FDR and the Secretary of the Interior, arranged for the concert to take place at the Lincoln Memorial. The concert had more than 75,000 live attendees and was broadcast on the radio. Among other selections, Ms. Anderson sang two of the other spirituals you will hear in our winter concert, “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord,” and “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” which she reportedly sang as an encore, with tears in her eyes.

As noted above, Ms. Anderson’s first recorded song was “Deep River” in 1924. The flip side was “My Way’s Cloudy.”

Both sides of Ms. Anderson’s 1924 record were arrangements by Henry (“Harry”) Thacker Burleigh, who published several arrangements of “Deep River” between 1913 and 1917. Burleigh was a classically trained composer and world-renowned baritone. When Burleigh first arrived in New York, he joined the men and boys choir at the Free African Church of St. Philip’s, which was less than a mile from Dvořák’s house and the National Conservatory of Music of America on East 17th Street. Burleigh was among the first of well over one hundred fifty African Americans whom Dvořák encouraged to enroll at the appproximately 600-student conservatory.

According to the Dvořák American Heritage Association:

Dvořák led the conservatory orchestra, which met twice a week. Burleigh served as the orchestra librarian and copyist, and filled in on double bass and tympani…. Dvořák and Burleigh apparently worked out well together. During his second year at the conservatory, Dvořák wrote to his family back in Prague that his son Otakar, age nine, “sat on Burleigh’s lap during the orchestra’s rehearsals and played the tympani.” Victor Herbert, a lifelong friend of Burleigh’s, described the Dvořák-Burleigh relationship in a letter sent in 1922 to Carl Engel, chief of the music division of the Library of Congress: “Dr. Dvořák was most kind and unaffected and took great interest in his pupils, one of which, Harry Burleigh, had the privilege of giving the Dr. some of the thematic material for his Symphony. … I have seen this denied – but it is true.”

Burleigh had learned many of the old plantation songs from the singing of his blind maternal grandfather, Hamilton Waters, who in 1832 bought his freedom from slavery on a Maryland plantation. Waters became the town crier and lamplighter for Erie, Pennsylvania, and as a young boy Burleigh helped guide him along his route. The family was Episcopalian and young Harry sang in the men and boys choir. Burleigh also “remembered his Mother’s singing after chores and how he and his [step] father and grandfather all harmonized while helping her.” At various times in his long life — he died in 1949 at age 81 — Burleigh described his student days with Dvořák. Taken together, Burleigh’s writings provide insight into Dvořák’s ongoing Negro music education while he was composing what would become the Symphony “From the New World”: “Dvořák used to get tired during the day and I would sing to him after supper … I gave him what I knew of Negro songs – no one called them spirituals then – and he wrote some of my tunes (my people’s music) into the New World Symphony.”

Dvořák began working on various “American” themes in mid-December 1892, filling eleven pages of a sketchbook. Burleigh wrote: “Part of this old ‘spiritual’ [‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’] will be found in the second theme of the first movement … given out by the flute. Dvořák saturated himself with the spirit of these old tunes and then invented his own themes. There is a subsidiary theme in G minor in the first movement with a flatted seventh [a characteristic passed on to jazz, known as a “blue note”] and I feel sure the composer caught this peculiarity of most of the slave songs from some that I sang to him; for he used to stop me and ask if that was the way the slaves sang.”

In January 1893, Dvořák began a continuous sketch for the “New World” Symphony. Wrote Burleigh, “When Dvořák heard me sing ‘Go Down Moses,’ he said, ‘Burleigh, that is as great as a Beethoven theme.'” This, for Dvořák, was the ultimate compliment. He made his students compose dozens of themes before accepting one as appropriate for “development.” He would then have them wrap the theme around the skeleton of an existing Beethoven sonata, imitating, measure by measure, the modulations and key relationships.

Dvořák began working on the full score in mid-February 1893. “Dvořák of course used ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,’ note for note,” continued Burleigh. “It was not an accident. He did it quite consciously … He tried to combine Negro and Indian themes. The Largo movement he wrote after he had read the famine scene in Longfellow’s ‘Hiawatha.’ It had a great effect on him and he wanted to interpret it musically”. [That Burleigh’s grandmother was part Native American may help to explain why Dvořák often equated or confused Indian with African American music.]